Ryan’s 50 Mile Run to Celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Foundation

In 2020, the Baltimore Bar Foundation turned 50 years old. Unfortunately, 2020 was not a good year for celebrations. So, as a belated celebration of that milestone (and as a fundraiser), on Sunday June 16, 2024, Foundation President Ryan Dietrich ran 50 miles throughout Baltimore City in a single day.

During the course of the 50 miles, Ryan stopped at 50 points of legal significance. Below is a chronicle of Ryan’s day, including a short explanation of why he stopped where he did. Please enjoy the history lesson – we guarantee you’ll learn something new!

Ryan’s run raised over $4,000 (and counting). That money will serve the Foundation’s efforts to fund grants to organizations that provide legal services to those in need in Baltimore, as well as support the Foundation’s scholarship, which is given annually to a Baltimore City public high school student who has expressed an intent to pursue a career in law. There is, of course, still time to give – you can do so at https://baltimorebar.intouchondemand.com/donation/donate

Ryan would like to thank the law firm sponsors (Diva Law, LLC; The Law Firm of J.W. Stafford; and Blibaum & Associates, P.A.), Derek Van De Walle (for his historical expertise), and Mac McComas (for running with him along part of the route). But most of all, Ryan would like to thank Karen Fast, Executive Director of the Foundation (and the Bar Association of Baltimore City), who provided much needed support throughout the (very long) day.

One note: the information below generally comes from publicly available online sources, including (and especially) Wikipedia. In some cases, entire sentences have been cut and pasted, so we do not necessarily claim these words as our own (the curation and aggregation is, however, Ryan’s own efforts).

Stop 1: Edward F. Borgerding District Court Building (5800 Wabash Ave) (Mile 0.0)

A journey of 50 miles begins with a single step. Here is Ryan (and trustee Linda Shields) outside the Edward F. Borgerding District Court Building in Northwest Baltimore. If you always thought it was just called “Wabash,” then you’ve already learned something new. But give the man his due: Edward Borgerding was an attorney and former Administrative Judge of the District Court of Maryland, in Baltimore.

This courthouse, completed in 1986, is one of four city courthouses housing the District Court of Maryland (as you’ll see, all of them were visited along Ryan’s route). The District Court of Maryland was created in 1971, by constitutional amendment, to replace a confusing system of local magistrates, justices of the peace, and People’s Courts, each with their own rules and procedures in the various counties. Under this simplified structure, the District Court is a statewide court with 33 locations in 12 districts, and is administered by one Chief Judge. As a general matter, the District Court (which falls on the bottom of the four tiers of Maryland courts) hears landlord/tenant cases, replevin actions (where you are trying to get property back from someone else), traffic violations and parking tickets, misdemeanor criminal cases (and some minor felonies), and civil cases in the amount of $30,000 or less (what people might call “small claims”). Wabash contains seven courtrooms and handles criminal matters. It houses the District Court Drug Treatment and Failure to Send Child to School dockets, as well as the Civilian Review Unit.

Stop 2: Gwynns Falls/Leakin Park (Windsor Mill Road) (Mile 3.25).

Just over three miles in was Ryan’s second stop: Leakin Park. Leakin Park admittedly has a somewhat macabre connection to the Baltimore legal scene, often playing the opening role in what will eventually become a murder prosecution. (For but one example, look to the Adnan Syed case) But despite its reputation, Leakin Park is an amazing gem of a park, created in the early 1900s with the help of the sons of noted landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead (who designed New York’s Central Park). Sadly, it is also notable in my view for how little it is in fact used. On the vast majority of my visits, one sees more deer than people. Such was the case today.

Leakin Park also holds a place in Baltimore legal history for what didn’t happen here. Many people know of the “highway of nowhere,” the one-mile multilane highway gutting the midsection of West Baltimore, but ending abruptly at the West Baltimore MARC station. Had the highway to nowhere continued as intended, it would have devastated large swaths of Leakin Park as it connected to I-70. But in 1971, a group of committed citizens sued in federal court to enjoin the construction of the portion of highway that would have traversed through Leakin Park. Appearing to appreciate the gravity of the players involved, the federal district court “reluctantly” concluded that the government had failed to comply with certain procedural requirements, and that the appropriate relief was to stop any construction of the highway. See Ward (the late Judge Thomas Ward) v. Ackroyd, 344 F. Supp. 1202, 1221 (D. Md. 1972). The government later abandoned the project.

Stop 3: Carroll Park (1500 Washington Boulevard) (mile 9.77)

Having left Gwynns Fall/Leakin Park, Ryan made his way along the Gwynns Falls trail until it encountered Carroll Park. The park is named for the Carroll family, which includes such illustrious members as Charles Carroll of Carrolton (1737-1832), one of the signers (and only Catholic signer) of the Declaration of Independence. There were apparently so many Charles Carrolls at the time that they each had to distinguish themselves. Carroll Park was the former estate of one of them, who took the name Charles Carroll, Barrister (1723-1783) (he was, in fact, a lawyer, though he apparently only practiced in England before coming to America). Ryan is pictured here in front of Mount Clare mansion, the summer home of Charles Carroll, Barrister.

Stop 4: Baltimore & Ohio Station (901 W Pratt Street) (mile 10.82)

As the first commercial passenger railroad (and one of the first railroads period), the Baltimore & Ohio railroad (which began here at this roundhouse) played an outsized role in the development of Baltimore and the nation as a whole. Many of the names synonymous with early Baltimore, such as John Garrett, George Brown, and Johns Hopkins, made their wealth in the railroads. And the railroads in turn played an outsized role in the development of the law, especially tort (i.e., personal injury) law. One commentator has opined that the development of tort law was “in large measure the result of railroading,” especially given that the leading cases “invariably involved railroad accidents.” (Remember Palsgraf v. Long Island Railroad?) The B&O also contributed to corporate law. Baltimore attorney John Van Lear McMahon drafted the B&O corporate charter, the first of its kind in the country.

Stop 5: Old Saint Paul’s Cemetery (Grave of Samuel Chase) (733 West Redwood Street) (mile 11.28)

Hidden next to the bustle of Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd is Old Saint Paul’s Cemetery. Although there are several important early Baltimoreans buried here, let’s focus on the most significant from a legal perspective. Samuel Chase (1741-1811) was not only a signer of the Declaration of Independence, but was also a justice of the United States Supreme Court. Chase is well-remembered for being the only Supreme Court justice to be impeached. His offense? That his political bias had infiltrated his judicial duties. He was subsequently acquitted, and many commentators have noted that this early unsuccessful attempt to impeach an official on grounds of political bias bolstered the principle of judicial independence and set a firm precedent against using politics as a basis for impeachment. We’ll see how firm that precedent is.

Fun fact: Chase was defended by Robert Harper, a US Senator and lawyer from Maryland, in his impeachment trial. Harper also represented Aaron Burr in his treason trial.

Stop 6: University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law (500 West Baltimore Street) (mile 11.6)

Was it 1816 or 1823 (or 1824)? Whatever year the school was founded, the University of Maryland’s law school is one of the oldest law schools in the nation. And best, of course. Although its prominent alumni are too numerous to name, they include an Attorney General of the United States, several United States senators (including our current Ben Cardin (and possibly our next one)), at least six Maryland governors, the owner of the L.A. Dodgers, Edgar Allan Poe (not the author but his cousin, the 26th attorney general of Maryland with the same name), a 50-miler runner, Elijah Bond, who patented the Ouija board, and too many judges to count. Ryan is pictured here with the current dean of the law school, Renée M. Hutchins.

Stop 7: Westminster Hall Burial Grounds (515 West Fayette Street) (mile 11.67)

Located within the same city block as the law school is Westminster Hall and Burial Grounds. Began as a graveyard in 1787 (with the church later erected over top the graveyard in 1852), most people know this location as the final resting place of Edgar Allan Poe (the famous author, not the 26th Attorney General of Maryland). But it is also the resting place of several other prominent early Baltimoreans, including a signer of the United States Constitution, James McHenry (1753-1816) (after whom Fort McHenry is named). Care of the premises was assumed by the University of Maryland law school in 1977.

Stop 8: Maryland State Bar Association (520 West Fayette) (mile 11.7)

One need only cross the street to arrive at the next stop. In a building formerly operated as “Male Grammar School No. 1” (a remnant of the original Baltimore City public school system—once the envy of the State) is the Maryland State Bar Association, Maryland’s voluntary bar association (voluntary in the sense that a barred attorney need not belong; instead, the Maryland Supreme Court is the entity that governs attorney licensing). Founded in 1896, the MSBA has served as the home of the legal profession in Maryland ever since. Ryan is pictured here with the executive director of the MSBA, Anna Sholl. (Note: although the MSBA maintains an office here, its main offices are now in Brewers Hill)

Stop 9: Ford’s Grand Opera House (Fayette between Howard and Eutaw) (mile 11.88)

This may be a parking garage today, but in 1872 it was the site of Ford’s Grand Opera House (owned by the same Ford as the infamous Ford’s Theatre in D.C.). And in that building was held the 1872 Democratic Party convention. What is so significant about that? Well, the Democratic party was in such shambles after the Civil War that they believed their best course to defeat the Republicans (represented by incumbent President Grant) would be to cast their support behind, and nominate as their own, the candidates of a splinter party called the Liberal Republican Party. (Jarring to today’s ears, they called themselves “liberal” because they believed that the regular Republicans were too “radical” for their tastes, particularly with regard to race relations.) Perhaps providing practical lessons that resonate to this today, this peculiar alliance was trounced, and President Grant easily won a second term.

Stop 10: Henry Fite House (NW corner Baltimore and Hopkins Place) (mile 12.04)

For two months over the winter of 1776-1777, after fleeing from Philadelphia under threat from the British, Baltimore served as the seat of government of what would become the United States. In Baltimore, the Continental Congress met at the Henry Fite House, an inn and tavern. It was during this period that George Washington famously crossed the Delaware and then won the battles of Trenton and Princeton, allowing the Continental Congress to return to Philadelphia. The Henry Fite House was later destroyed, like many others, during the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904. Today, it is the site of the Civic Center, Baltimore Arena, 1st Mariner Arena, Royal Farms Arena, CFG Arena.

Stop 11: Hooper’s Restaurant (SW corner of Charles and Fayette) (mile 12.24)

In 1960, a group of African-Americans went to Hooper’s Restaurant, which was on this site, to engage in a “sit-in” protest of the owner’s racially discriminatory policies. This group was arrested and subsequently convicted of criminal trespass. Although their convictions were affirmed in the then-Maryland Court of Appeals, Bell v. State, 227 Md. 302 (1962), the United States Supreme Court granted certiorari review to consider questions of equal protection and due process. The U.S. Supreme Court, however, did not grapple with these substantive questions, instead concluding that, because Maryland had since enacted a public accommodations law (under which Hooper’s discriminatory policies would have been illegal), their convictions should be vacated under common law principles relating to repealed laws and non-final judgments. Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1964). The “Bell” whose name graces the case caption is, of course, Robert M. Bell, who rose through all four levels of the judiciary to become Chief Judge (Justice) of the then-Maryland Court of Appeals (now Maryland Supreme Court).

Grantee Shoutout: Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service/Homeless Persons Representation Project (201 North Charles Street) (mile 12.28)

As stated in the introductory post, the Baltimore Bar Foundation awards grants to organizations that provide legal services in Baltimore City. This is the headquarters of two of those organizations. First, the Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service (MVLS) “directly helps Marylanders facing legal challenges, while also fighting to change systems that harm people living in or near poverty,” through “pro bono representation, community engagement, and legislative and administrative advocacy.” The Homeless Persons Representation Project’s (HPRP) “mission is to end homelessness in Maryland by providing free legal services, including advice, counsel, education, representation and advocacy, for low-income persons who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.” The HPRP began under the auspices of MVLS in 1987 but later became its own organization.

Stop 12: Office of the Attorney General of Maryland (200 St. Paul Place) (mile 12.35)

The Attorney General is the chief legal officer of the State of Maryland. The Attorney General’s Office has general charge, supervision, and direction of the legal business of the State, acting as legal advisor and representative of the major agencies, various boards, commissions, officials and institutions of State government. The Office also enforces the State’s antitrust, consumer protection and securities laws, and conducts criminal prosecutions and appeals. Unlike in our federal system (where the Attorney General is appointed by the President), the Attorney General in Maryland is elected by the voters. Although the office dates back to Maryland’s first constitution in 1776, the office was actually abolished by constitutional amendment in 1817 (though reestablished by legislative act that same year). The office was reestablished as a constitutional office in the Maryland Constitution of 1864 (and retained in our fourth and current Constitution, adopted in 1867 – although it’s been amended several times since). Currently occupying the office of Attorney General is Anthony Brown (pictured with Ryan), who is the State’s 47th, yet first African-American, Attorney General.

Stop 13: Etta Maddox (corner of Lexington and St. Paul) (mile 12.36)

Margaret Brent (c.1601-1671) is known today as Maryland’s (and the nation’s) first woman lawyer. She was an English immigrant who appeared before the common law courts of Maryland in colonial times.

But times changed, and at the turn of the twentieth century women were prohibited by law from being admitted to the Maryland bar (and thus could not practice law in Maryland courts). This changed with Etta Maddox (1860-1933). Although Maddox was initially denied admission to the bar by the Maryland Supreme Court, (In re Maddox, 93 Md. 727 (1901)), she successfully lobbied the General Assembly to change the law. She was admitted in 1902 after passing the bar examination, and practiced in her office here at the intersection of Lexington and St. Paul streets.

Maddox argued her first case in the Circuit Court for Baltimore City on December 14, 1904, where she successfully secured her client $3.50 a week in alimony and a $15 counsel fee.

Maddox was also involved in the women’s suffrage movement. As a founder of the Maryland Suffrage Association, organized in 1894, she authored Maryland’s first suffrage bill, which did not pass. Maryland women were not afforded the right to vote until the United States Constitution was amended in 1920.

Times seem to be changing once again. Sixty six percent of the incoming class of the University of Baltimore School of Law are women (similarly, 60% of Maryland’s incoming class are women).

Stop 14: Everett Waring (217 St. Paul Street) (mile 12.44)

From the first woman (barred) attorney to the first African-American attorney. In 1885, a group of community activists challenged the section of the Maryland constitution barring Black lawyers from practicing in the state courts. At that time, a man named Charles S. Wilson applied for admission to the bar of the Baltimore City Superior Court. The court rendered an unprecedented, unanimous decision that “color alone would never bar a person from receiving justice within its limit and jurisdiction.” Nonetheless, the judges (who at the time were authorized to admit individuals to the bar) decided that Wilson was not fully qualified for admission. The activists rushed to Howard University to convince Everett Waring to come to Baltimore and make history. On October 10, 1885, Waring did, becoming the first African American lawyer admitted to the bar of the Maryland courts. Waring decided to remain in Baltimore, and practiced law here on this site (217 Courtland (now St. Paul street)).

It should be noted that, in 2023, the Maryland Supreme Court posthumously admitted a man named Edward Draper to the Maryland bar. Draper, an African-American man who was otherwise found qualified to practice law in Maryland, had been denied admission in 1857 solely because he was not a White man. Draper then left the State and died the following year.

Stop 15: Maryland Office of the Public Defender (201 St. Paul Place) (mile 12.51)

The Maryland Office of the Public Defender provides free representation to indigent individuals facing criminal prosecution (and child removal proceedings). Like all other public defenders’ offices, it has its origins in the 1963 United States Supreme Court case of Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), which held that the Sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution requires States to provide an attorney to criminal defendants who are unable to afford one. Although many States initially responded to this mandate through an ad hoc system of appointed private counsel, in 1971 the Maryland General Assembly created the Maryland Office of the Public Defender as an independent state agency. Currently leading the office is Natasha Dartigue (pictured with Ryan), who just happens to be the incoming president of the Baltimore Bar Foundation for the 2024-2025 fiscal year.

Stop 16: Statue of Cecil Calvert (St. Paul Street between Lexington and Fayette) (mile 12.59)

Yes, this picture is taken outside of a courthouse, but more on that later. For now, this stop is at the statue of Cecilius Calvert (1606-1675), the second Baron of Baltimore (here, referring to a place in Ireland anglicized from Baile an Tí Mhóir, rather than the city here in Maryland, which would not be founded in any of its forms until the 18th century). Cecilius was the son of George Calvert, who had long sought to found a colony in the New World to serve as a refuge for English Roman Catholics. That goal became a reality when King Charles I granted a proprietary colony to Cecilius in 1632. Interestingly, Cecilius (like his father, who died before the charter was issued) never actually set foot in Maryland.

Unlike Virginia (which, after 1624, was a Crown Colony), Maryland was a proprietary colony. This meant that, rather than administer the colony directly, the King issued a charter to an individual proprietor or company, who would in turn have authority over its management. And the model for the Maryland charter was that of the Palatinate of Durham, a relic of the Middle Ages that had given the Bishop of Durham (within the bounds of English territory) practically royal power over city. Thus was the beginning of a sense of independence. In return, all that the Calverts owed the King were an annual gift of two Indian arrow heads, and a fifth of all the gold and silver discovered in the territory (which apparently turned out to be none).

As for the statue itself, it is not an accurate depiction of Cecil Calvert. The artist used native Baltimorean and major silent film star Francis X. Bushman as a model.

Stop 17: District Court of Maryland Commissioner’s Office (1 North Charles Street) (mile 12.7)

One of the lesser known players in the judicial process is the Commissioner. This position is a judicial officer involved in conducting initial appearances, issuing charging documents, summonses and warrants, setting and accepting bonds, or determining conditions of pre-trial release for arrested persons within the District Court. Thus, whether you are arrested for a crime or wish to charge someone with a crime (or get an interim protective order), the Commissioner is oftentimes a person’s first point of contact with the criminal judicial system. Although most commissioners are housed within some of the District Court courthouses, in this building is Baltimore City’s freestanding “Centralized Application Station,” which has Commissioners available 24 hours/7 days a week.

Stop 18: United States Attorney’s Office (36 South Charles Street) (mile 12.86)

The Judiciary Act of 1789 divided the nation into federal judicial districts, with Maryland and most states each being one district (in contrast, today there are 94 districts in the 50 states and territories). The Act also established the office of the United States Attorney for each district. The United States Attorney is the chief federal law enforcement officer in their district and is also involved in civil litigation where the United States is a party. In Maryland and elsewhere, the office may be best known for its prosecution of violent crime (especially gang crime), as well as its prosecution of public officials for corruption.

Each United States Attorney is appointed by the President of the United States. The current United States Attorney is Erek Barron, who is Maryland’s first African-American United States Attorney.

Stop 19: Edward A. Garmatz United States District Courthouse (101 W. Lombard Street) (mile 12.96)

Completed in 1976, this building houses the judges and courtrooms of the Northern Division of the United States District Court for the District of Maryland (the courthouse for the Southern Division is in Greenbelt). In common parlance, it is Baltimore’s “federal courthouse.” Like many of the nation’s original federal judicial districts (established by the Judiciary Act of 1789), Maryland started out (and stayed that way until 1910) with only one federal judge for the entire state (the first judge was none other than William Paca, a signer of the Declaration of Independence). There are now 16 active judges (including senior judges) on the court.

The building is named for Edward Garmatz (1903-1986), a congressman who served Maryland’s third district from 1947 to 1973.

Stop 20: Statue of Thurgood Marshall (intersection of Pratt and Hopkins) (mile 13.07)

Right outside of the federal courthouse is a statue of Thurgood Marshall, which is by artist Ruben Kramer and was dedicated in 1980. Thurgood Marshall was born in Baltimore in 1908 (we’ll visit his boyhood home later). Although Thurgood Marshall applied to the University of Maryland law school, he was denied admission on the basis of his race. Marshall instead went to Howard, where he was mentored by Charles Hamilton Houston. After law school, Marshall returned to Baltimore to practice law, where he became involved with the NAACP. One of his notable cases was Murray v. Pearson, 169 Md. 478 (1936), which achieved for Donald Murray what he could not for himself: admission to Maryland Law. Executing a widespread strategy against racial discrimination in all facets of life, Marshall’s efforts with the NAACP culminated in the landmark Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), which unanimously rejected the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson and struck down racial discrimination in education. Marshall was then appointed by President Kennedy to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (the federal appeals court covering New York, Connecticut, and Vermont), and later by President Johnson to the position of Solicitor General of the United States (the office whose attorneys argue in front of the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of the United States). Ultimately, in 1967, Marshall was nominated and confirmed to the United States Supreme Court as its first African-American justice. Marshall served on that court for nearly 24 years until his retirement in 1991.

Stop 21: Camden Yards Sports Complex (333 W Camden Street) (mile 12.32)

Although the stadiums may have a tenuous connection to the law, they are such great features of the City that they deserve a spot on this list. But, at least with regard to the Orioles, there is a legal connection. First, the Orioles (formerly the St. Louis Browns) were brought to town in 1954 by a team led by Baltimore attorney Clarence Miles (founder of prestigious Baltimore law firm Miles & Stockbridge, P.C.). Then, in 1979, the team was sold (for $12 million) to lawyer Edward Bennett Williams (founder of the prestigious Williams & Connolly law firm). It was then sold (for $70 million) in 1988 to a team fronted by Eli Jacobs (a lawyer) and that also included Maryland attorney Sargent Shriver (who was JFK’s brother-in-law); in 1993 a group led by famed asbestos lawyer Peter Angelos bought the team at an auction (for $173 million) after Jacobs went bankrupt; and, just this year, the team was bought (for $1.75 billion) by a group led by businessman (and lawyer) David Rubinstein. The current ownership team also includes: lawyer (and former Baltimore mayor) Kurt Schmoke, who was the State’s Attorney for Baltimore City from 1983 until 1987; and Cal Ripken, who, while not a lawyer, is married to a judge (Laura Ripken, of the Appellate Court of Maryland).

Stop 22: John R. Hargrove, Sr. Courthouse (700 East Patapsco Ave) (mile 18.81)

It took a while from the last stop, but Ryan’s next stop was in Brooklyn at Hargrove, which is another courthouse housing Maryland’s District Court. As noted previously, the District Court (which falls on the bottom of the four tiers of Maryland courts) hears landlord/tenant cases, replevin actions (where you are trying to get property back from someone else), traffic violations, misdemeanor criminal cases (and some minor felonies), and civil cases in the amount of $30,000 or less. Judges at this courthouse hear criminal matters, and the building houses the District Court Mental Health Court.

The building is named after John R. Hargrove, Sr. (1923-1997), the first African American to be appointed Assistant United States Attorney for the District of Maryland and who was later appointed as a judge on the United States District Court for the District of Maryland.

Stop 23: Fort McHenry (War of 1812/Civil War) (2400 East Fort Ave) (mile 23.77)

After another long stretch, including a trip over the Hanover Street bridge and through what is now called Baltimore Peninsula, Ryan arrived at Fort McHenry. Fort McHenry is of course famous for the defense of Baltimore under bombardment by the British during the War of 1812. After burning down Washington, DC in August 1814, the British had set their sights on Baltimore. They first landed at North Point, where they were met by American forces, whose efforts delayed the British advance. At the same time, the British fleet sailed to Fort McHenry and relentlessly bombarded it over the course of the night of September 13th. On September 14, 1814, the fort was still standing; the Americans raised a 30ft by 42ft flag to prove it. Observing that flag from a British ship was American lawyer Francis Scott Key, who was on board in an effort to secure the release of a friend who had been captured. Key then wrote what he titled “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” later published as “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Although the song was popular and gained the status as the de facto national anthem by the time of the Mexican American war, it was not finally adopted as the official national anthem until 1931.

Fort McHenry is also notable for its part in the Civil-War-era legal case of Ex Parte Merryman. After the Baltimore Riot of 1861 (discussed later in this series), President Lincoln delegated authority to the Army to suspend habeas corpus in Maryland (meaning that individuals could be held without the government having to justify the detention to the courts). During this time, John Merryman had been arrested in 1861 for destroying railroad bridges that Union soldiers were using to travel through Maryland. Like several other Southern-sympathizing Baltimore officials (including the entire city council, mayor, and police commissioner), Merryman was held at Fort McHenry without access to the civilian legal system. Because a prior order from a federal district court judge to produce a different prisoner had been ignored by the military commander at Fort McHenry, Merryman’s lawyers went straight to Chief Justice Taney of the U.S. Supreme Court to ask for a writ of habeas corpus. Chief Justice Taney (in his role as circuit judge, i.e., the Supreme Court judge overseeing a particular judicial district) issued a writ commanding the military commander to produce Merryman in court in Baltimore. When the commander asked for more time, Taney held him in contempt and issued an order (a writ of attachment) commanding that he be brought before the court. (But because a U.S. marshal was refused entry into the fort, the writ of attachment was never served).

Taney then issued a decision, which stated that the President cannot suspend habeas corpus; rather, it must be done, if at all, by the Congress. Taney sent the decision to President Lincoln, “in order that he might perform his constitutional duty, to enforce the laws, by securing obedience to the process of the United States.” Lincoln, however, refused to obey, setting up a constitutional showdown. Merryman was ultimately released, however, and the matter did not proceed any further. Because Taney’s opinion was not precedential, the constitutional question of who has the right to suspend habeas corpus, Congress or the president, has never been officially resolved.

Partner Organization Shout-out: Maryland Legal Services Corporation (Charles Center) (mile 26.7)

The Maryland Legal Services Corporation was created by the General Assembly in 1982 as a nonprofit corporation to distribute funds for the provision of civil legal services to low-income Marylanders. Historically, and primarily, MSLC is funded by interest on the trust accounts that lawyers (mainly in private practice) must maintain to hold client funds. Today, MLSC also receives funding from surcharges on certain court filing fees and a distribution from the Abandoned Property Fund.

Stop 24: Baltimore City State’s Attorney Office (120 East Baltimore Street) (mile 26.86)

Before 1851, the job of enforcing the laws in Maryland was mainly done by the Attorney General (which at that time was a legislatively-created position). But that year Marylanders enacted a new constitution (its second), which created the position of State’s Attorney for each county and Baltimore City. This new constitution thus effectively gave the State’s Attorney in each jurisdiction the role that the Attorney General had previously provided. When a new constitution (Maryland’s third) was enacted in 1864, the Attorney General position was revived as a constitutional office. But the position of State’s Attorney remained, as that office was charged generally with “perform[ing] such duties . . . as are now or may be hereafter be proscribed by law[.]” Today, along with various powers, the law charges the State’s Attorney to, “in the county served by the State’s Attorney, prosecute and defend on the part of the State all cases in which the State may be interested.” Crim. Proc. 15-102. What this means in practice is that the State’s Attorney prosecutes all state-law criminal offenses committed within the City. Pictured here with Ryan is Ivan Bates, the current State’s Attorney for Baltimore City.

Stop 25: Baltimore City Hall (100 N Holliday Street) (mile 27.03)

Baltimore’s distinctive City Hall was completed in 1875 and, with a façade built from marble quarried from Baltimore County, is a wonderful example of Second Empire architecture. Here, the Baltimore City Council engages in the legislative process for making the laws of the City. Interestingly, none of the current (or soon-to-be) 15 members of the council is a lawyer. In contrast, two of the last six mayors have been lawyers, although sadly it can said that two of the last six mayors have needed to retain lawyers.

City Hall is home to the Baltimore City Law Department, which provides legal services to the City. Former City Solicitors include John E. Semmes (founder of Semmes, Bowen & Semmes), Simon Sobeloff (Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals of Maryland and a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit), George Russell Jr. (first African-American to serve as associate judge of the Supreme Bench of Baltimore), Andre Davis (former judge on the federal district court and Fourth Circuit). The current City Solicitor, Ebony Thompson, is the first woman and openly gay person to serve in the role.

Grantee shoutout: Maryland Legal Aid (500 East Lexington) (mile 27.13)

Another one of the Foundation’s grantees, Maryland Legal Aid provides low-income people in the State of Maryland a full range of free civil legal services, including child custody, housing, public benefits, consumer law (bankruptcy and debt collection), and criminal record expungements. By numbers, Maryland Legal Aid is one of the largest law firms in the State. In 2022, Maryland Legal Aid served over 100,000 individuals and families.

Stop 26: Juvenile Justice Center (300 N Gay St) (mile 27.29)

The Baltimore City Juvenile Justice Center, which opened in 2003, is a multi-purpose building that houses courtrooms for the circuit court (which is the trial-level court that has jurisdiction over juvenile matters) as well as offices for various officials and social services. The building also serves as a detention center for male youth detainees.

Stop 27: Fayette Street courthouse (501 East Fayette Street) (mile 27.62)

Yet another location of the District Court of Maryland, the Fayette Street courthouse houses the civil division. This courthouse thus handles all minor civil matters including landlord tenant disputes, housing violations, and minor civil suits.

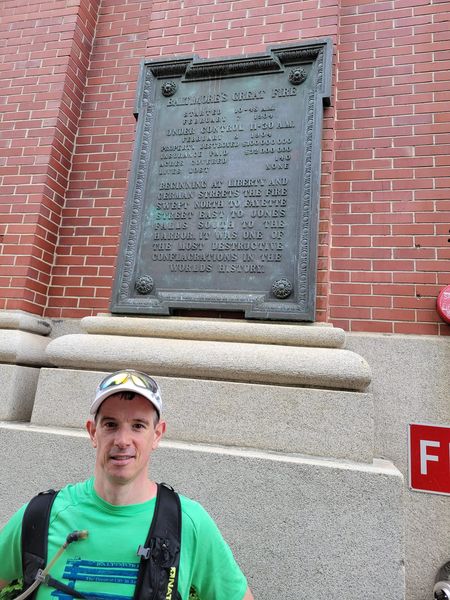

Stop 28: Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 (Plowman Street) (mile 27.87)

The Baltimore of today is much different than the Baltimore one would have encountered 120 years ago. That’s because in February of 1904 a fire ravaged through downtown Baltimore, destroying 1,500 buildings over 14 acres. Indeed, there are very few structures in downtown (at least east of Howard Street) that can claim to have been built before 1904. The fire resulted in estimated property damage of $100 million (but miraculously no direct loss of life). And, interestingly, the historical marker here near the Jones Falls (whose natural features prevented the fire from spreading further east) has deemed it necessary to note that only $32 million in insurance was paid. But the legal implications extended beyond any litigation over the damages of the fire: Baltimore finally adopted a building code (that stressed fireproof materials), and the National Fire Protection Association adopted a national standard for fire hydrant and hose connections. This latter action was spurred by the fact that, although firefighters from surrounding areas had responded to assist, they were unable to do so in any meaningful way because their equipment was not compatible with the hydrant connections in Baltimore.

Stop 29: Former site of Maryland Institute College of Art (Marketplace between Baltimore Street and Water Street) (mile 27.9)

Before it moved to its current site on Mount Royal Avenue, the Maryland Institute College of Art (then known as the Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts) was located here on this site. But what does a college of art have to do with law? Well, in June 1852, Baltimore—and MICA in particular—could have been considered the center of the American political universe. From June 1st through 5th, 1852, the Democratic Party held its political convention on its campus, nominating eventual general election winner Franklin Pierce (a former U.S. Senator from New Hampshire). Interestingly, Franklin, a dark horse candidate, did not receive any votes until the 35th ballot, and was the eventual winner only on the 49th ballot. Because of his inability to prevent the nation from dissolving into strife over the issue of slavery, Franklin is considered one of the worst presidents in American history.

But what makes MICA memorable as a stop is that, less than two weeks after the Democrats nominated Pierce, MICA was also the scene of the convention of the other major political party at the time, the Whigs. The Whigs were a major political party from the 1830s until the 1850s, coming into existence as essentially a conglomeration of disaffected members of other parties. At the 1852 Whig convention, the party nominated General Winfield Scott (who was a general during the War of 1812 and also commanded the U.S. Army in the Mexican-American War). After the Whigs lost the general election, the party collapsed, and did not field its own candidate in the 1856 presidential election.

Stop 30: Site of the Second Bank of the United States (40 South Gay Street) (mile 28.03)

On this site in 1818 was the Baltimore Branch of the Second Bank of the United States. In that year, the State of Maryland passed a law that imposed a $15,000 tax on any bank operating in Maryland that was issuing notes and bills that were not properly stamped by Maryland’s treasury. After James William McCulloh, a cashier at the bank, issued unstamped bank notes to a Baltimore resident, an informer sued, hoping to collect a bounty. The Maryland state courts concluded that, because there was no specific constitutional authorization for the federal government to create a bank, the bank itself was unconstitutional. In the seminal case of McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819), the United States Supreme Court, in an opinion by Chief Justice Marshall, held otherwise. The Court held that the Necessary and Proper clause of the Constitution gives the United States government certain implied powers that are necessary and proper for the powers that are otherwise explicitly enumerated in the Constitution. In a famous passage that would guide interpretation of the document, Chief Justice Marshall remarked: “[W]e must never forget, that it is a constitution we are expounding.” The Court also established, to the extent it was not already clear, that state action may not impede valid constitutional exercises of power by the federal government.

Bonus stop: USCGC Roger B. Taney (Pier 5) (mile 28.35)

USCGC Roger B. Taney is a United States Coast Guard High Endurance Cutter that is notable as the last warship floating that fought in the attack on Pearl Harbor. It is named after Roger B. Taney (1777-1864), who served as Attorney General of Maryland (1827-1831), United States Attorney General (1831-1833), Secretary of the Treasury (1833-1834), and fifth Chief Justice of the United States (1836-1864). Taney was of course the author of the notorious Dred Scott decision (1857), in which the Supreme Court held that African-Americans were not intended to be included within the word “citizens” as used in the Constitution, and could “therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.” In 2020, the current owner of the ship, Living Classrooms Foundation, removed Taney’s name so that the ship is now referenced as WHEC-37.

Stop 31: Baltimore Riot of 1861 (601 President Street) (mile 28.8)

One of Baltimore’s nicknames is “mobtown,” which by its nature denotes the absence of law (and order). Although the origin of the name stretches as far back as the Federal period (especially surrounding the War of 1812), one of the major events of disorder that defined Baltimore as “mobtown” was the Baltimore Riot of 1861, which started here at the President Street Station. A week after the fall of Fort Sumter, President Lincoln put out a call for soldiers for purposes of putting down the rebellion. On April 19, 1861, the 6th Massachusetts Militia arrived at President Street Station via the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore (PW&B) Railroad. Their problem: they had to cross the city to get to Camden Station (adjacent to Camden Yards) to continue their journey south on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. This logistical deficiency meant a slow journey of more than a mile through the City as the railroad cars were pulled by horse. The City’s residents at the time, however, were strongly “pro-Southern,” and opposed their city being used to further the war effort. So not surprisingly, when the soldiers began their trek through the City, a mob of Southern sympathizers attacked the train cars and blocked the route. The soldiers got out of the cars and, in response to continuing attack by the mob, fired into the crowd. A giant brawl ensued, and although the soldiers eventually got to Camden Station, five soldiers and 12 Baltimore citizens lay dead in the wake.

George William Brown, at the time Mayor of Baltimore City, tried to stop the violence by marching in front of the soldiers with his umbrella. Despite this heroic act, he was imprisoned, without trial, for much of the Civil War. Brown founded the Library Company of the Baltimore Bar and the Baltimore, and served as Chief Judge of the Supreme Bench (1873-1888) and president of the Bar Association of Baltimore City.

The carnage of the Baltimore Riot of 1861 inspired the poem “Maryland, my Maryland,” which later became the state song in 1939. In light of its glorification of the Confederate cause, its status as state song was rescinded in 2021.

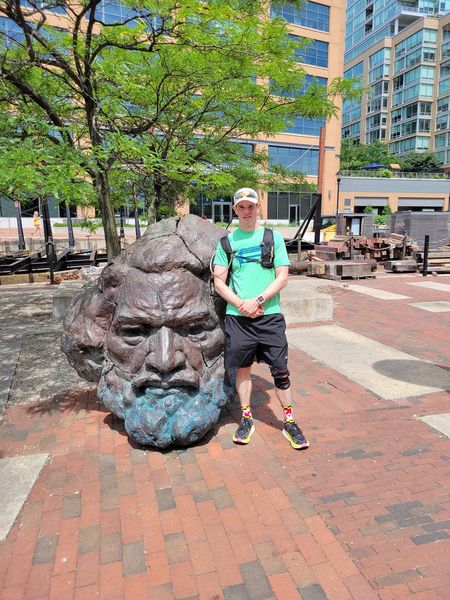

Stop 32: Fells Point/Frederick Douglass (1417 Thames Street) (mile 29.38)

Frederick Douglass (c.1817-1895) was not a lawyer, but his life had an incredible impact on the Nation’s legal trajectory as it shed its original sin of slavery. Although Douglass was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore, as a boy he arrived in the Fells Point neighborhood to serve the Auld family. It was there that he first learned to read and that the power of knowledge was “the pathway from slavery to freedom.” He also was employed as a caulker in the shipyards of Fells Point. In September 1838, and after obtaining identification papers from a free Black sailor, Douglass boarded a train in Baltimore and escaped to New York City. In 1841 Douglass met William Lloyd Garrison, one of the leading abolitionists of the day, and became an anti-slavery lecturer himself. In 1845, Douglass published his “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” which described in unprecedented detail the abominable nature and moral toll of slavery.

Bonus note: Like Leakin Park (stop 2), Fells Point was also targeted for destruction to make way for a highway. And like Leakin Park (but unlike West Baltimore), Fells Point activists, among them future Senator Barbara Milkulski, were successful through litigation in blocking the planned highway.

Stop 33: John Barron’s Wharf (intersection of Wolfe and Lancaster) (mile 29.85)

This is just a nondescript intersection where Wolfe Street meets Lancaster Street in Fell’s Point, but in the early 1800s this was the site of John Barron and John Craig’s wharf, which had the “deepest water in the harbor.” However, in paving and re-grading streets from 1815 to 1821, the City of Baltimore diverted a stream from its natural channels. The resulting deposits of sand and gravel in the basin lessened the depth of the water at the Barron and Craig wharf. Barron sued, and a jury found that the city’s action had materially impaired the value of the wharf, awarding him $4,700 on the authority of the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution. In 1833 the jury verdict was overturned by the United States Supreme Court, which held that the provision of the Fifth Amendment declaring that “…private property [shall not] be taken… without just compensation” was solely a limitation on the exercise of power by the government of the United States and not a limitation on the exercise of power by state or local governments. In other words, the Court ruled that the Bill of Rights, and the rights it protected, did not apply to the States (although it should be noted that many states, including Maryland, had their own declarations of rights in their state constitutions). It was not until the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, and the subsequent doctrine of selective incorporation was developed, that (most of) the Bill of Rights applied to the States.

Bonus Stop: Patterson Park (intersection of Eastern and Patterson Park Ave) (mile 30.67)

This was another stop with a somewhat tenuous connection to Baltimore legal history, but is nonetheless a great place for a stop. At a fundamental level, Patterson Park did play a role in preserving our nation and its independence from Great Britian. When the British attempted to invade the City in 1814 as part of the Battle of Baltimore (after being delayed at the Battle of North Point), the northwest high point of the park (then called Hampstead Hill), served as a defensive position that repelled them. Because of this defensive effort, and because the British fleet was prevented at Fort McHenry from advancing close enough to provide artillery support, the British retreated. Three months later, the war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent (though the Battle of New Orleans was famously fought in January 1815 after the war had officially ended).

Patterson Park is named after William Patterson, a wealthy merchant and a founder of the B&O Railroad. In 1827, he donated the first five acres of land that became Patterson Park. William Patterson is also the father of Elizabeth “Betsy” Patterson, who had a short-lived marriage to Jerome Bonaparte (younger brother of Napoleon). Elizabeth and Jerome had one son, Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte, who in turn had a son, Charles Bonaparte, a prominent Baltimore attorney. Charles became U.S. Attorney General and then Secretary of the Navy under President Theodore Roosevelt, and he was also the founder of the Bureau of Investigation (which would become the FBI).

Stop 34: Eastside/North Avenue Courthouse (1400 North Ave) (mile 33.07)

This is the fourth and final District Court courthouse on the route. If it doesn’t look like a courthouse, that’s because that was not its original use. Instead, this was formerly a Sears store, which closed in 1981. As a reminder, the District Court (which falls on the bottom of the four tiers of Maryland courts) hears landlord/tenant cases, replevin actions (where you are trying to get property back from someone else), traffic violations, misdemeanor criminal cases (and some minor felonies), and civil cases in the amount of $30,000 or less. Judges at this court hear criminal matters. The courthouse also houses the Veteran’s Court and the Domestic Violence Unit of the State’s Attorney’s Office.

Stop 35: Green Mount Cemetery (1501 Green Mount Avenue) (mile 33.35)

Green Mount Cemetery is synonymous with Baltimore history. Dedicated in 1839, it was at the forefront of the rural cemetery movement, which moved away from the concept of the dreary church cemetery and toward a more park-like setting. Indeed, these rural cemeteries, much like parks, provided people with a place to enjoy outdoor recreation amidst art and sculpture previously available only to the wealthy. (Not today though: the cemetery’s website states that “[r]unning, playing, and noisy activities are not appropriate.”)

The cemetery is a resting place for several individuals of legal significance, including James Bartol (1813-1887), Chief Judge of the Maryland Court of Appeals (1867-1883); Carroll Bond (1873-1943), Chief Judge of the Maryland Court of Appeals (1924-1943); Elijah Bond (1847-1921), lawyer and patentor of the Ouija board; John Archibald Campbell (1811-1880), Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court (1853-1861 – he concurred in the Dred Scott decision); Allen Dulles (1893-1969), director of the Central Intelligence Agency and a member of the Warren Commission; Benjamin Chew Howard (1791-1872), reporter of decisions of the United States Supreme Court (1843-1860); Reverdy Johnson (1796-1876), Attorney General of the United States (1849-1850), the lawyer for the slave owner in the Dred Scott case, Andrew Johnson in his impeachment trial, and Mary Surratt (a Lincoln-assassination conspirator) in her treason trial; John Nelson (1794-1860), Attorney General of the United States (1843-1845); John Prentiss Poe (1836-1909), Attorney General of Maryland (1891-1895); Severn Teackle Wallis (1816-1894), first president of the Bar Association of Baltimore City; and Etta Maddox (1860-1933) (who was discussed at stop 13). Green Mount is also notable as the burial site of John Wilkes Booth (1838-1865), who assassinated President Lincoln.

Stop 36: Terrapin Park (intersection of 30th and Barclay) (mile 34.74)

Before Oriole Park at Camden Yards (and before Memorial Stadium), there was Terrapin Park, which stood here near the intersection of 30th Street and Barclay Street. Terrapin Park was the home of the Baltimore Terrapins, one of the most successful teams in the short-lived Federal League of professional baseball from 1914-1915. At that time, the City had a minor league team called the Orioles (the earlier major league Orioles had left town in 1903, destined to morph into what is now the New York Yankees), which played across the street in a stadium called Oriole Park. But there wasn’t room enough in town for two teams, and by 1915 the minor-league Orioles had left town for Richmond, and the Federal League (and the Terrapins) went belly-up. Claiming that the established American and National leagues had interfered with their business (and that the Federal League had also stiffed them), the Baltimore Terrapins (under their official name, the Federal Base Ball Club of Baltimore, Inc.) sued, claiming that the other leagues had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act. The Terrapins won in the district court, but the Court of Appeals held that baseball was not subject to the Sherman Act. Then, in a unanimous decision authored by Justice Holmes, the United States Supreme Court affirmed, holding that “the business of giving exhibitions of base ball . . . are purely state affairs,” and thus fail to supply the predicate “interstate commerce” necessary to give rise to a federal antitrust action. This holding will be jarring to the ears of any first-year law student, who knows that “interstate commerce” encompasses a nearly boundless scope. Nonetheless, although the Supreme Court has since acknowledged that Major League Baseball is in fact engaged in interstate commerce, it has declined to overturn its exemption from antitrust laws, deeming it necessary to preserve precedent. And so this “precedential island” endures to this day.

Bonus stop: Baltimore City College (mile 35.54)

Opened in October 1839, Baltimore City College is the third-oldest active public high school in the United States. Its graduates include many pillars of the Baltimore legal community, including numerous judges (including four former judges of the Fourth Circuit).

Each year, the Baltimore Bar Foundation partners with College Bound to provide a college scholarship for a Baltimore City public high school student who expresses an interest in pursuing a career in law. Recipients of the scholarship have included students from Baltimore City College.

Stop 37: Memorial Stadium (900 East 33rd Street) (mile 36.09)

On this site used to stand Memorial Stadium, home to both the Baltimore Orioles and the Baltimore Colts. The Baltimore Colts, of course, famously left in the middle of the night on March 29, 1984, relocating to Indianapolis. One of the reasons they left under such circumstances: Because two days earlier, the Maryland Senate had overwhelmingly approved legislation that would have allowed the City to seize the team through eminent domain. When that legislation was signed into law only a few hours after the team was gone, the city began the nearly unprecedented step (Oakland had attempted it with the Raiders) of initiating condemnation proceedings against the Colts. But in December 1985, a federal court ruled against the City, concluding that it could not exercise eminent domain over “property” that was no longer within the State. Baltimore v. Baltimore Football Club, Inc., 624 F. Supp. 278 (D. Md. 1985).

Memorial Stadium was built on a site called Venable Park, named after Richard Venable, who oversaw the purchase of the land for a City park. Venable founded the firm Venable, Baetjer & Howard, now simply known as “Venable LLP.”

Pictured with Ryan is Teresa Epps Cummings, the incoming president of the Bar Association of Baltimore City for fiscal year 2024-2025.

Stop 38: Johns Hopkins University (3400 N Charles Street) (mile 37.14)

With almost 40 miles in the books, Ryan arrived at the campus of Johns Hopkins University, a private university founded in 1876. Although Hopkins does not have a law school, its graduates include many notable legal figures, including Benjamin Civiletti (1935-2022), former Attorney General of the United States (1979-1981).

Grantee shoutout: Community Law Center (3355 Keswick Rd) (mile 38.17)

Another one of the Foundation’s grantees, the Community Law Center is located here in Hampden. It touts itself as the “legal partner to neighborhoods and nonprofits in pursuit of more just and vibrant communities.” Through its network of over 500 pro bono attorneys, it provides all levels of direct legal representation, ranging from helping a community organization obtain 501(c)(3) tax exemption status to undertaking years-long litigation on behalf of community leaders, to trainings in best practices for nonprofit Boards.

Stop 39: Roland Park (Roland Ave and Cold Spring Lane) (mile 40.16)

Ryan traveled north to Roland Park, one of the first garden suburbs in the nation. But, although the neighborhood is not unique in this, Roland Park shares a regrettable legacy of legally sanctioned racial discrimination. In 1910, the City passed a law that stated that it was illegal for any person of color to move into a house on a block that was more than 50 percent White. The owners of the Roland Park Company, who created the Roland Park neighborhood out of woodlands, shared that sentiment. But rather than rely on Baltimore’s law, the Roland Park Company inserted covenants into their deeds that restricted owners from selling to African Americans. And because the Roland Park Company retained the ability to approve sales, they were able to maintain an unwritten policy of excluding Jews as well. This strategy was much more long-lasting than the City law, which, like others around the country, was struck down in 1917 by the United States Supreme Court (apparently on the theory that it restricted the White seller’s constitutional freedom of contract, Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917)). Instead, racial covenants were not struck down by the United States Supreme Court until 1948 (this time, on Equal Protection grounds, Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)). But the practical effects on the racial housing patterns in the City endure to this day.

Bonus stop: Baltimore Polytechnic Institute (mile 40.56)

Founded in 1883 as a school for instruction in engineering, Baltimore Polytechnic Institute (known as “Poly”) is currently located here at the corner of Falls Road and Cold Spring Lane. Despite its focus in the sciences, Poly also counts many notable legal figures among its alumni.

Each year, the Baltimore Bar Foundation partners with College Bound to provide a college scholarship for a Baltimore City public high school student who expresses an interest in pursuing a career in law. Recipients of the scholarship have included students from Poly.

Grantee shoutout: Pro Bono Resource Center/Disability Rights Maryland/Druid Hill Park (1500 Union Ave) (mile 41.53)

Pictured here is the Union Mill building, which is adjacent to Druid Hill Park and houses two of the Foundation’s grantees: the Pro Bono Resource Center (PBRC) and Disability Rights Maryland.

PBRC is the Maryland State Bar Association’s “pro bono arm” and provides a unique state-wide role as a training, support, innovation, and advocacy center for pro bono work.

Disability Rights Maryland is a nonprofit organization that advances the civil rights of people with disabilities by providing free legal services to Marylanders of any age with all types of disabilities (developmental, intellectual, psychiatric, physical, sensory, learning, traumatic brain injury), who live in facilities, in the community, or who are homeless.

Bonus stop: William Wallace statue (Druid Hill Park) (mile 43.81)

Druid Hill Park has four statues, including one of William Wallace, the Scottish patriot famously portrayed by Mel Gibson in Braveheart (1995). As depicted in the film, Wallace was caught and tried for treason by the English authorities. But Wallace had what he thought was a good defense: he could not be guilty of treason because he had never declared allegiance to King Edward. Wallace was executed anyway.

Mentioned a few stops ago was Richard Venable, who founded the Venable law firm. As President of the City Park Board, Venable was responsible for adding over 800 acres of park land to the City, including expanding Druid Hill Park. When Venable died in 1910, he was cremated. Legend has it that his ashes were scattered in Druid Hill Park.

Stop 40: University of Baltimore School of Law (1401 N Charles St) (mile 45.68)

The other law school in the State was founded in 1925 as part of the then-private, nonprofit University of Baltimore. It was created to serve the working population of the Baltimore area with a part-time evening program. The school, however, added a full-time day division in 1969. In September 1970, the University of Baltimore School of Law merged with Eastern College and its Mount Vernon School of Law, which was founded in 1935. On January 1, 1975, the school became a public institution when the University of Baltimore joined the University of Maryland system. Prominent alumni include Peter Angelos, disgraced Vice President Spiro Agnew, the fictional Cedric Daniels from the HBO show The Wire, and numerous Maryland judges and politicians.

Stop 41: Thurgood Marshall House (1632 Division Street) (mile 47.0)

Ryan is pictured here in front of the boyhood home of Thurgood Marshall at 1632 Division Street. As discussed at an earlier stop, Marshall, though rejected on the basis of his race from the University of Maryland School of Law, rose to prominence as the preeminent civil rights lawyer of the 20th century. After prevailing in the Brown v. Board of Education case striking down racial discrimination in education, Marshall went on to be a judge on the Second Circuit, Solicitor General, and finally an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court.

Stop 42: Mitchell Law Offices (1239 Druid Hill Avenue) (mile 47.38)

Ryan is pictured here at 1239 Druid Hill Avenue, which was the site of the law offices of Juanita Jackson Mitchell (1913-1992), the first Black woman to practice law in Maryland. Mitchell graduated from the University of Maryland School of Law in 1950 (the first Black woman to do so), and thereafter took on civil rights case in Baltimore and throughout the State. In 1938, she married Clarence Mitchell, Jr., a civil rights activist whose name we will see in an upcoming post. Together, they began a political dynasty that endures to this day.

Although the building shows sign of neglect, there are big plans in store. With the help of federal funding, the building will soon be renovated as the Juanita Jackson Mitchell Law Center. The Center will have as a tenant the Rebuild, Overcome, and Rise (“ROAR”) organization, which provides holistic, client-driven services, including legal support, to survivors of crime.

Stop 43: The Wire (McCulloh Homes, 1051 McCulloh Street) (mile 47.7)

It’s not even close – the Wire is the best show ever produced for television. Over the course of five seasons, it depicted—with incredible authenticity and depth—the complexities of urban life through the lens of law enforcement, drug dealers, dock workers, politicians, the schools, and journalists. And although it is of course set in Baltimore, and (accurately) portrayed the idiosyncrasies of the City, the themes and contemporary dilemmas that it explored, including those related to the law, were universal.

Ryan is pictured here in West Baltimore at the McCulloh homes, which (most prominently during Season One) provided the backdrop for the “Pit,” where the Barksdale crew ran their drug operations.

Stop 44: Empty Statue Base (Mount Vernon Square) (mile 48.45)

For the last seven years, this has been an empty block. But until it was removed in 2017, and for 130 years before that, the block held a statue of Chief Justice Roger Taney. If you paid attention to the discussion of Taney several stops back, you’ll know that Taney played the central role in the Dred Scott Supreme Court decision, which represents a dark part of American history and is regarded as one of the chief reasons why the nation accelerated into civil war over slavery. Taney’s statue was removed as part of a general cleansing of the city of Confederate (and, in this case, Confederate-adjacent, since Taney did, to his credit, stay loyal to the United States) monuments in 2017.

Stop 45: Severn Teackle Wallis statue (Mount Vernon Square) (mile 48.55)

Severn Teackle Wallis, who is memorialized in a statue here in Mount Vernon Place, was a founding member, and first president of, the Bar Association of Baltimore City. So far so good. But he was also imprisoned in Fort McHenry (see prior stop) for failing to cite an oath to the Union before a secession vote. And Wallis spoke glowingly of Taney when Taney’s statue (since removed) was unveiled on the grounds of the Maryland State House (a copy of which adorned the empty statue base that was the subject of the previous stop).

Stop 46: Maryland Penitentiary (Death Chamber) (954 Forrest Street) (mile 49.13)

Now known as the Maryland Metropolitan Transition Center, this building (formerly known as the Maryland Penitentiary) houses Maryland’s decommissioned death chamber (the capital prisoners were themselves housed in a prison in Western Maryland). After the General Assembly abolished the death penalty in 2013, in 2014 Governor O’Malley commuted the sentences of the four remaining death-row inmates to life without the possibility of parole).

Stop 47: Baltimore Basilica (religious toleration) (409 Cathedral St) (mile 50.12)

Maryland is generally known as having been founded on the ideals of religious toleration. As noted earlier, the Calverts obtained the charter for Maryland as part of their goal of establishing a haven for English Roman Catholics in the New World. Cecilius Calvert’s instructions to the first governors and officials of Maryland contained a warning that the Catholic and Protestant residents of Maryland were not to give offense to one another in the matters of religion. An early high water mark of religious toleration came in 1649, when the freemen of Maryland approved An Act Concerning Religion, stating that “no person or persons whatsoever within this province . . . professing to believe in Jesus Christ shall from henceforth be in any ways troubled, molested, or discountenanced for or in respect of his or her religion, nor in the free exercise thereof….” Given the aftermath of the religious wars in Europe in the early part of the 17th century, this Act truly was remarkable.

Unfortunately, things went downhill for a bit. As the English Civil War (1642-1651) heated up, and as Catholic James II was defeated (1688) and replaced by William and Mary (and the Act of Settlement of 1701 ensured that only a protestant could occupy the English throne), the spirit of religious toleration dimmed. But Maryland retained its Catholic character, and was the site of the first Catholic cathedral in the United States, which was built in 1806 and still stands at this spot.

Stop 48: Clarence M. Mitchell, Jr. Courthouse (100 North Calvert) (mile 50.5)

Located on the west side of Calvert Street, the Mitchell Courthouse is one of two courthouses housing the Circuit Court for Baltimore City. The Mitchell Courthouse was dedicated in 1900, and replaced a previous courthouse that was on Calvert Street. The Courthouse is in the Renaissance Revival style, and the exterior is constructed of white marble quarried in Cockeysville. The interior contains several notable features, including the ceremonial courtroom, the Museum of Baltimore Legal History, the Bar Library, and several murals of notable lawgivers. On March 8, 1985, the courthouse was rededicated as the “Clarence M. Mitchell, Jr. Building,” honoring a man who, as chief lobbyist for the NAACP, was nicknamed the “101st U.S. Senator.”

As noted above, today the building houses the Circuit Court for Baltimore City, which, like circuit courts around the State, is a court of general jurisdiction (and with appellate jurisdiction over many cases from the District Court). This one-stop-shop is all that remains from a lengthy history of various courts that had various jurisdictions. For example, in its illustrious history, Baltimore City had at one time all of the following: a Court of Oyer and Terminer (a sort of criminal court back when Baltimore City was part of Baltimore County), a Court of Common Pleas (like a small claims court), a Superior Court (a court with larger civil jurisdiction), a Criminal Court (self-explanatory), the Circuit Court for Baltimore City (similar to the Superior Court), Circuit Court No. 2 (like the original circuit court), the Baltimore City Court (first a criminal court, then abolished and recreated to handle civil matters), a Juvenile Court (self-explanatory), and the Supreme Bench (which had an administrative role, among others). Happily for Maryland’s citizens and legal professionals alike, in 1983 all of the remaining courts were consolidated into the Circuit Court for Baltimore City. Thus, today Maryland’s state trial judiciary (whether in Baltimore City or elsewhere) is comprised only of the District Court (minor criminal offenses, small civil claims, and some extraneous things such as landlord/tenant) and the Circuit Court (everything else, i.e., a court of general jurisdiction).

Stop 49: Elijah E. Cummings Courthouse (111 N Calvert Street) (mile 50.5)

Formerly Courthouse East, the Cummings Courthouse on the east side of Calvert Street began its life as a federal building housing a Post Office and the United States District Court for the District of Maryland. It was completed in 1932 and boasts a classic design and a Spanish-style roof. Then, in 1978 the building was deeded to the City to house facilities for its circuit court. In 2020, the courthouse was renamed for Elijah Cummings, a 12-term congressman and noted civil rights activist from West Baltimore.

In addition to housing circuit court courtrooms and judges, the Cummings Courthouse houses the chambers of several appellate judges, including a justice of the Maryland Supreme Court (formerly the Court of Appeals). Although it was renamed as the Supreme Court of Maryland in 2022, the Court was created through the first Maryland Constitution in 1776. Beginning with five justices, the Court now has seven members. And from its early beginnings, each justice has represented a particular judicial district, thus giving the Court an intentional geographical diversity. Until 1966, the Court was Maryland’s only true appellate court. Today, other than certain specialized appeals (such as legislative redistricting), the Supreme Court hears cases only by way of writ of certiorari: this means that the Court, much like the United States Supreme Court, generally gets to pick and choose which cases it hears. As a result, the Court generally hears only cases of great significance. The Supreme Court hears cases in its courtroom in Annapolis.

The other appellate court is the Appellate Court of Maryland (formerly known until 2022 as the Court of Special Appeals). In 1966, the General Assembly, pursuant to its constitutional powers, created this court, which at first heard only criminal appeals (thus its “special” nature). But in 1974, the jurisdiction of the Appellate Court was expanded so that it could hear civil appeals as well. The Appellate Court is comprised of 15 judges, some of whom represent particular judicial districts and some of whom are “at-large.” The Appellate Court generally hears cases as panels of three judges. The Cummings Courthouse houses the chambers of two active judges on the Appellate Court of Maryland.

Finally, the Cummings Courthouse houses the Orphan’s Court for Baltimore City. With an anachronistic name, this court specializes in handling cases involving wills and estates, as well as matters involving the assets and guardianship of children.

Some notable legal events occurred in the Cummings Courthouse, including: (1) 1934: Judge W. Calvin Chestnut became the first jurist to strike down a New Deal Act of Congress; (2) 1948: Alger Hiss filed a libel suit against Whittaker Chambers; (3) 1973: Vice President Spiro T. Agnew pleaded nolo contendere to tax evasion and resigned as vice president under Richard M. Nixon; and (4) 2010: After this site was serving as a city site of state court, Baltimore Mayor Sheila Dixon was tried by the Office of the State Prosecutor and found guilty.

Stop 50: Bar Association of Baltimore City/Baltimore Bar Foundation (111 N Calvert Street) (mile 50.5)

Ryan’s journey finished in front of the Cummings Courthouse, which houses the offices of the Bar Association of Baltimore City (and by extension the offices of the Baltimore Bar Foundation). One of the oldest bar associations in the country (older even than the Maryland State Bar Association and just a year younger than the American Bar Association), the Bar Association of Baltimore City was founded in 1879. The Bar Foundation, as we learned at the beginning, was founded in 1970. Pictured with Ryan is Karen Fast, the Executive Director of the BABC (and by extension the Foundation).

We hope you have enjoyed touring Baltimore’s legal history. We circle back to our original ask: If you have learned something today, or otherwise feel compelled, please make a donation to the Baltimore Bar Foundation to support its work and the scholarship that we offer to Baltimore City public school students who express an intent to go into the field of law. You may be setting the stage for the next great legal event in Baltimore history.